This is the third post in our series on effective Digital Health Systems.

Part one is Effectiveness, or Oops! We failed Again and part two is Outing Net Outcomes

We know most of you won’t be that interested in the economic principles behind much of what we’re writing about, but here’s a post for those of you who are.

What makes a thing a public good anyway?

There’s a famous1 paper called The Pure Theory of Public Expenditure by Paul Samuelson that was the first one to answer this question in a formal way. He comes up with two criteria for something to be a public good: Non-exclusivity and Non-rivalry.

What and what? Non-exclusivity means that you can’t really stop people from using it. Non-rivalry means that one person’s use of it doesn’t reduce the amount available to another person.

The classic example is a lighthouse – you can’t cover it up so only some boats can use it, and one boat using it doesn’t reduce the amount available for another boat.

But here’s the point behind the point: the implication is that if something is a public good, then it should be built and maintained by public institutions.

We worked out lighthouses are valuable, and we worked out there’s no model to sell the service a lighthouse provides. Then we took the next step: we decided that governments of some form or other need to both build and run them. Not controversial.

Digital Public Goods to the rescue?

So we’ve taken the language and concepts of public goods and made these things called Digital Public Goods.

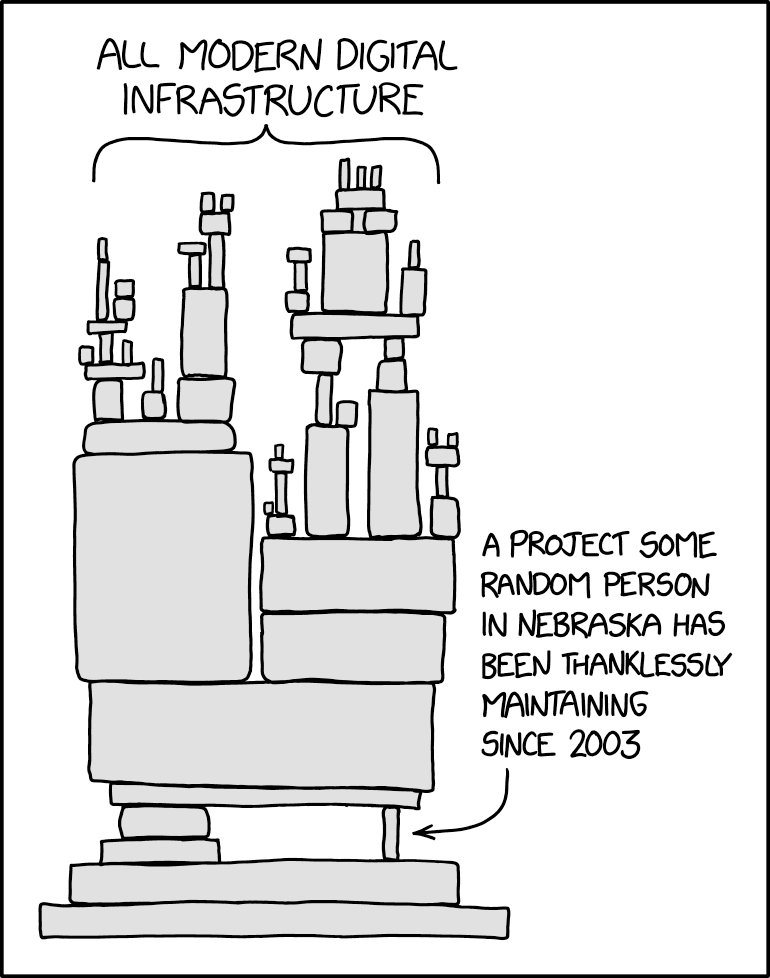

It makes sense when you think about it, open source software fits the definition of a public good: One person using it doesn’t diminish the amount available to others, and once it’s open source, it’s free for anyone to use.

But but but: what we haven’t really grappled with is the implication for building and maintaining these goods: that if something’s going to work as a public good, someone has to commit to funding both the building and the maintaining of it..

There’s no shortage of organisations that have set themselves up as curators or gatekeepers for Digital Public Goods. They’re here and here and here.

But none of them really address the “how do we fund and maintain them?” question (as far as we can see).

Digital Square has (had?) this spreadsheet that lays out three levels of funding maturity:

- Low: At most two revenue streams exist. Revenue streams are largely dependent on time-bound project implementations

- Medium: Multiple revenue streams/funders exist across project implementations

- High: Multiple revenue streams and funding mechanisms exist, including at least one that provides for multi-year support of core software development, documentation and other key artifacts.

To us it feels like this requirement to have “multi-year support of core software development, documentation and other key artifacts” should have not been put on the public goods themselves, but rather on the plate of those who are promoting public goods as the path forward for countries. Making the public goods solve the problem is a bit like beating up the lighthouse keeper because the government didn’t pay the electricity bill for the lighthouse ;-)

On the other hand, the recent evaporation of the world’s largest funder in this space highlights the problem that even with a larger funder, important projects are at the mercy of a change in policy.

So, what’s the answer? Is there an answer? Next week’s blog will try and lay out a way forward that’s robust, fair and importantly cost effective!

1 This is a questionable use of “famous”

fn2. Those looking for irony might find a fertile field in assessing the sustainability of the gatekeepers themselves.